Note: This piece was originally published December 2012 in Positively Filipino, a new online magazine celebrating the story of the global Filipino. The magazine title is taken from an infamous sign posted on the front door of a Stockton, California hotel in the 1930s. The sign read, “Positively No Filipinos Allowed.”

A couple of weeks ago, I met for the first time the editorial group, led by founder and former Filipinas Magazine publisher Mona Lisa Yuchengco and managing editor Gemma Nemenzo. My fellow contributors are a lovely bunch; I encourage you to visit the site and read their pieces.

A few days ago I was out late with my friend E at Barrio Lastarria. It must have been around three or four in the morning and we were already—or only, given the place and time—half-drunk.

“Maybe El Toro will still be open,” E suggested, since around us the pubs and cafés were either closed or closing. So we walked north toward Parque Forestal, an eerily beautiful park created on reclaimed land from the Mapocho River, on our way to Loreto Street in Bellavista, the sleepless bohemian barrio of Santiago, Chile.

At the park we noticed a group of four young men in hoodies who had emerged from leafy shadows and appeared to be following us. One of them carried a bat of some sort: the baseball or cricket sort. A few seconds later, a fifth man—slightly older, but no more than thirty, with a shaved head—also seemed to come from nowhere and began to walk even more hurriedly in our direction.

“Jacket, please,” E began to say, in a tone that verged on being hysterical. “Your jacket! Put it on.” A clueless, silly foreigner, I did what he asked me to do while the fifth man caught up with us. He approached with a kind of swagger, with a cocky little smile that to me looked less amiable than threatening. Addressing E, he inquired, “¿Qué hora es?”—as if there were a train to catch, an appointment to make, or a deadline to beat; as though it was the most common thing in the world to be asking for the time in the dead of the night-morning while the rest of the city slept or got lost in the heady blur of cervezas and vinos.

It was only after E gave the time and, without warning, plucked my sleeve and we burst out running, as fast and as far out of the park as we could, without looking back, without bothering to check where and who the chasers were, if indeed they chased and not simply stood there laughing at us—it was only after this sudden, harrowing half-minute that E told me we had just escaped neo-Nazis.

At the mention of this I positively shivered. Neo-Nazis in Chile are known to discriminate against a wide range of minorities, including homosexuals, Peruvian immigrants, punk rockers, alcoholics, drug addicts, even whites from southern Europe. About Asians I don’t know how they feel exactly, but I won’t hesitate to say that the scare at the park could have turned into something perilously worse. Last March, neo-Nazis killed a twenty-four-year-old Chilean gay man named Daniel Zamudio. They attacked him in Parque San Borja, which is also along Alameda, five minutes away from Parque Forestal. There were four attackers; according to reports, they beat Daniel up for an hour, broke both his legs, cut off one of his ears, seared his skin with cigarettes, pounded his head with a stone, and carved swastikas on his abdomen using the neck of a broken bottle of pisco sour. He died a couple of weeks later in the hospital.

“I’m sorry we had to go through that,” said E, who is gay. The apology was not necessary. What was he saying sorry for? I was alive and unharmed. Though jolted sober with hearts still pounding, we were alive. As though to relish this fact, we sat on a sidewalk on Dardignac Street in Bellavista and simply stayed there for at least two hours, only getting up just before the sun rose.

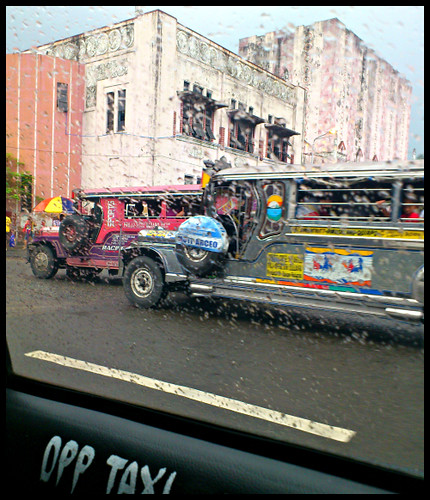

A sidewalk: when I came eleven thousand miles from Manila to work in Santiago, I well expected to feel transplanted—to spend my days in a state of perplexity and unbelonging. I expected correctly. Save for a graphic designer who recently left for Nagpur in India, I have not met another Filipino. There is, in fact, nothing here that can be described as being from home or of home: there isn’t a single Filipino restaurant, a single Filipino club, a single Filipino anything. More than once I have wondered if, as a temporary resident of Chile, I may as well be living in another planet.

Like E, I also happen to be gay. This makes it almost impossible for me to be any more a ‘minor’ than I already am (unless I tried to like punk rock, which I believe I am too old for), and indeed if there was a place in Santiago where I belonged, at least as much as E did, it certainly would not be Parque Forestal, among Chilean neo-Nazis roaming, waiting, moving to pounce.

Yet—yet—as we sat later on concrete in the wee hours of the morning, I began to wonder if there was a more profound way of gaining and strengthening one’s sense of identity than to encounter people bent on disagreeing with it; if, in the face of fear, or amid threats of intolerance, hatred, and discrimination, one might suddenly become more honest and frank about himself. “You don’t look Chilean,” E said when I asked, half-jokingly, if I could pass for one. Of course not—and I always knew it. But never have I felt more exceptionally Filipino than here on the streets of Santiago, under the glare of people who are shockingly non-Asian, and never has the fact of my sexuality asserted itself more swiftly than when I was made to grasp, both by telling and by reimagining, the heartbreaking tragedy that befell Daniel Zamudio.

E told me that he was one of thousands who lit candles the day Daniel died. Shortly after that Chilean President Sebastian Piñera accelerated the passage of an anti-discrimination law designed to prevent hate crimes and violations of fundamental human rights. I was still in Manila then, occupied by the comforts and entanglements of the Filipino commonplace. But if somehow there was a way to reach out to the dead, to the murdered, I’d say to Daniel, thank you for your life. My journey across thousands of miles no longer seems so distant, and I can be more fearless roaming the world you had left.